“What has caused this great commotion, motion, motion,

Our country through?

It is the ball a-rolling on,

For Tippecanoe and Tyler too.

Tippecanoe and Tyler too.

And with them we'll beat the little Van, van, van;

Van is a used-up man,

And with them we'll beat little Van!”

The attendant carriage, quadrupeds, bipeds and the rustic

procession, rumbled through the streets and entered Salem, threading its way

and finally reaching the crowded common.[9]

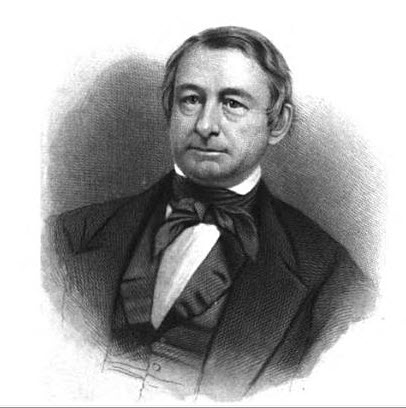

An aristocratic Whig of the old school as well as an outstanding

statesman, orator and lawyer, Daniel Webster held the crowd with his great

skill. Commenting on the “humble birth of their candidate for the Presidency”

he said, “It did not happen to me, gentlemen, to be born in a log-cabin; but my

elder brothers and sisters were born in a log-cabin, raised amid the snow-drifts

of New Hampshire, at a period so early that, when the smoke first rose from its

rude chimney and curled over the frozen hills, there was no similar evidence of

a white man's habitation between it and the settlements of the rivers of

Canada. It remains still exist. I make to it an annual visit; I carry my

children to it, to teach them the hardships endured by the generations which

have gone before them. I love to dwell on the tender recollections, the kindred

ties, the early affections, and the touching narratives and incidents which

mingle with all I know of their primitive family abode. I weep to think that

none of those who inhabited it are now among the living; and if ever I am

ashamed of it, or if ever I fail in affectionate veneration of him who reared it

and defended it against savage violence and destruction, cherished all the

domestic virtues beneath its roof, and, through the fire and blood of a seven

years' Revolutionary war, shrunk from no danger, no toil, no sacrifice, to serve

his country and to raise his children to a condition better than his own, - may

my name and the name of my posterity be blotted for ever from the memory of

mankind!”[10]

Although Webster was not a leader the citizens voted for, he was

highly esteemed and respected and the people of Massachusetts were honored when

he was asked by Harrison to serve in the Whig cabinet as Secretary of State.

Rufus Choate was chosen to complete Webster's term in the U.S. Senate. In

November, Salem and Danvers celebrated. Buildings were illuminated as

victorious Whigs took to the streets. Some disappointed Democrats assembled

outside of their headquarters on Central Street and as the procession of

celebrants passed by, they hooted and jeered.[11}

As President of the Senate, Daniel received an invitation from the

Whigs of Boston to the Grand Ball held at Faneuil Hall “to celebrate the

accession of General Harrison to the Presidency of the United States.”[12]

It seemed the celebrating had barely stopped when the Whigs suffered

an unbearable disappointment. After a month in the White House, Harrison, the

oldest President ever inaugurated, died. John Tyler of Virginia became the

“accidental” President.