Chronology:Events

of the decade leading up to the publication of the Wizard newspaper.

Fig. 4.1. Daniel Putnam

King

4 FEBRUARY 1850

Leaders

The town’s representative in Congress, DANIEL P. KING, wrote to his family

on Lowell Street from Washington D.C.. “The House adjourned and we heard

a great speech from HENRY CLAY on the desirableness of the Union.

The hall was crowded and many had stood three hours to hear him.

The Southern men generally feel very bitter and very determined to rule

or ruin all, but I shall not flinch. They will get not more concession

and no more slave power with my consent.”

15 FEBRUARY 1850

National The new Fugitive

Slave Law prompted a mob to rescue SHADRACH, an accused fugitive, from

Boston jail. The government mandated that the fugitive must be returned

as outlined by the law, which angered many Northerners.

10 JULY 1850

National News of the death of PRESIDENT

ZACAHARY TAYLOR arrived by telegraph. MILLARD FILLMORE assumes office.

25 JULY 1850

Leaders DANIEL P. KING died unexpectedly

at his home on Crystal Lake. The House of Representatives formally announced

King’s death two days later and many tributes were offered in remembrance

of the “fervid and earnest pleas for liberty and human rights", which

King uttered on the floor of Congress.

6 MAY 1852

Leaders LOUIS

KOSSUTH (1802-1894), the leader of the 1848 Hungarian revolution against

Austria, visited the Lexington Monument at Main and Washington streets.

He compared the patriots of the American Revolution with the Hungarian

patriots seeking independence from the czar of Russia.

20 AUGUST 1853

Education On another hot, sunny

day, the cornerstone of the new Peabody Institute was laid on Main Street.

The ceremonies were attended by several dignitaries.

As requested

by GEORGE PEABODY, the cornerstone was laid by industrialist ABBOTT LAWRENCE

along the northwest angle of the site. He said, “We have a great

labor yet to perform. We live in a country increasing in the number

of its people at the rate of a million a year! And, our only security for

the preservation of our freedom and our republican institutions is to educate

the people. Not only let there be education, but let it be universal

– a universal education of the people – and this is the purpose of the

institution whose foundation-stone we are called upon to place today.

It is one of the germs of this universal education.”

7 JUNE 1855

Government The first town meeting

was held and sixty-three men were elected to various posts. The fire

department has six hand fire engines, six hose carriages, a sail

carriage, and one hundred and eighty members.

9 OCTOBER 1856

George Peabody A cone of streamers

of various colors festooned from the peak of the roof of the one-year

old Peabody Institute on Main Street to mark the parade and reception for

GEORGE PEABODY held jointly by Soutb Danvers and Danvers.

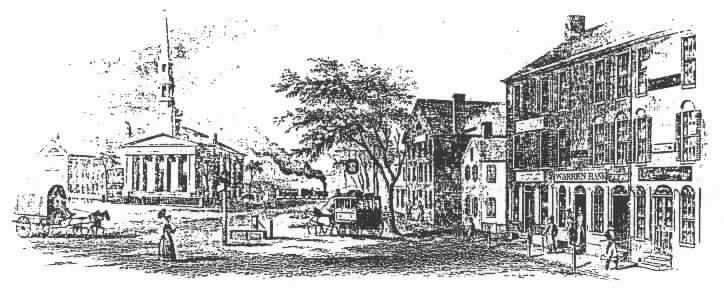

Fig. 4. 4 The Square during

the 1856 Parade and Reception for George Peabody

Fig. 4. 4 The Square during

the 1856 Parade and Reception for George Peabody

Peabody moved

in an elegant carriage drawn by six horses and proceeded to the parade

route. Visiting the Institute on Main Street the following day,

he “entered his name as an applicant for books.”

A crowd of people

met him at the square in Danvers when he left. “A chain of little

children holding hands had stopped his carriage. He bowed to the

people and thanked the citizens for the public honors he had received.”

14 AUGUST 1857

George Peabody It was a sea

of stove pipe hats and bonnets, parasols and fans – thousands of people

in the humid heat jostling each other while they scrambled to get a seat

on one of the coaches that arrived every five minutes. The dust and

smell of horses filled the air in the Square.

A few days before

sailing for England, George Peabody agreed to revisit his birthplace.

A simple picnic for three thousand, “Mr. P” called it the highlight

of his visit.

It took place

about a mile and half from the square at King’s Grove, in spite of the

lowering and doubtful weather. All the citizens of the town, old

and young, were invited to the gathering where swings and seats were tucked

in the field and forest. Eighteen tables were arranged which set

end-to-end would have measured close to one thousand feet. They were

covered with cloth from the Danvers Bleachery, and were spread with offerings

provided by the women of the town.

NOVEMBER 1857

Leaders

JAMES BUCHANAN was elected fifteenth President of the United States.

4 JANUARY 1858

Education The new school

on Central Street was dedicated. Two years later it was named in

honor of NATHANIEL BOWDITCH (1773-1838), who attended school in that area

as a child. Born in Salem on March 26, 1773, Bowditch moved to Danvers

as an infant.

“His paternal

ancestors had been shipmasters for several generations, but his father

retired from that occupation, and became a cooper. He began to manifest

remarkable faculties at an early age although he stopped attending school

at the age of ten. He acquired the Latin and French languages

for the sake of translating Newton’s Principia and La Place’s Mechanique

Coleste, and arrived at a height of Mathematical greatness far above his

contemporaries.

“His work on

practical navigation is the best in the world and is used universally by

American sailors. Difficult problems and the abstruse windings of

Mathematics were his passion, and those calculations which were inscrutable

to other men were sport to him.

“He navigated Salem

Harbor in a small pleasure boat for the purpose of experiment and rendered

his conclusions susceptible of demonstration.”

He died one of

the most remarkable men of his day, March 16th, 1838, at age sixty-five.

An ancient landmark,

a pine tree that was significant in the minds of residents even after it

disappeared, was located near where Bowditch spent his childhood. The townspeople

said the tree was at his root.

The tree was described as having long

arms stretched out near its top and as being deprived of branches below.

It was “an old settler of the forest totally unlike any other tree around

it” and its age was unknown. It was believed that it was a familiar

object to those who came to the hanging tree in Salem to witness the execution

of the witches in 1692.”

In the 1700’s,

the giant pine tree fell to the earth. “That old pine tree is associated

in our minds by many early recollections - not that we ever saw it, for

it was gone long before our time - but its name remained,” reported the

Danvers Courier.

“Its memory is cherished, embalmed in the hearts of our townsmen,

It stood at a corner, at one of the outposts of our village. Everybody

who knew anything, knew about the pine tree. It gave character and

consequence to the neighborhood about it. Travelers were directed

by it. Citizens venerated it and its fame become immortal!

“We have said

we never saw the pine tree, but in our boyhood, we had our designs of ambition

and wished to stray into foreign parts and unknown regions. We had

as great longing to see the pine tree as ever had Columbus to see the New

World. How did our little hearts beat and our eyes dance when under

the paternal guidance, we had the promise of a ride to - aye - beyond the

pine tree. It was only a place, a name, an immortal name and perhaps

it is engraven all the deeper in our memory for the disappointment.”

JUNE 1858

Education Under the district school

system, each school was provided for and maintained by the residents of

the surrounding neighborhood, which caused great disparity in the quality

of education. School districts were renamed:

District 1: Wallis School

District 2: Center School

District 3: Bowditch School

District 4: Rockville School

District 5: Locust Dale School

District 6: Felton School

District 7: West School

District 8: Suntaug School

16 AUGUST 1858

Life/Customs President JAMES BUCHANAN

and QUEEN VICTORIA exchange greetings across the newly laid Atlantic cable.

11 NOVEMBER 1858

Arts/Culture RALPH WALDO EMERSON

lectures on “Memory” at the Peabody Institute.

1 DECEMBER 1858

Life/Customs The occasion of the

“Dinner of the Rocks”, one of the most characteristic and successful practical

jokes pulled off by town humorist FITCH POOLE.

“In the early

days of the Peabody Institute lectures, Professor Hitchcock, “an eminent

geologist”, delivered a course of lectures and while in town he was entertained

by Fitch Poole. A large number of the people of the town were invited

to meet him at a party at Poole’s home on Main Street.

“When the time

for refreshments arrived, the company was ushered into a well supplied

supper room, and just at that moment the host was called away for a moment,

and excused himself with a cordial invitation to his guests to help themselves

of the good things before them.

“After the first

descent upon the table, a strange embarrassment stole over those who endeavored

to dispense the refreshments. One would take off the cover from a

dish, and hastily replace it; another found the oysters of surprising weight

and texture; the cake could scarcely be lifted; the ice creams and custards

could be carried about bodily by the spoons inserted in them; each new

dish was more puzzling than the last. At length it dawned upon the

brighter spirits, that here was truly a geological feast, and the laugh

began.

“The oysters

were pudding-stone; the cake was brick, frosted with plaster of Paris;

custards and creams were of plaster colored and molded; sugar, cream, every

detail of the banquet was of mineral origin, of plaster, or stone or clay.

When the fun began to subside, another door was thrown open, and a more

edible repast was spread before the guests.”

6 APRIL 1859

Education An act to abolish the

school district system was approved by the state legislature. It

required the town to provide and maintain the schools.

16 JULY 1859

Leaders Death of RUFUS CHOATE

Fig 4.6 Rufus Choate

l

(1799-1859) The keynote speaker at the

dedication of the Peabody Institute, Choate was a local lawyer and legislator

who went on to serve in the U.S. Congress. While there, he was a

prime influence in establishing and defining the Smithsonian Institute

- seven years before the Peabody Institute on Main Street opened.

The Smithsonian Institute

was created in 1846, when, over the protests of some, the Congress voted

to accept a half-million dollar bequest to establish an institute in Washington

for the “increase and diffusion of knowledge among men.”

The gift was made by

JAMES

SMITHSON, the wealthy, illegitimate son of a European Duke. He had

no connection with the United States.

In the Senate, the

bequest was assigned to the Library Committee, of which Choate was a member.

He argued that a plan championed for an institution for the teaching of

natural history, chemistry, astronomy and science, would result in “a pretty

energetic diffusing of the fund; not much diffusion of knowledge.”

Instead, he proposed

a program of lectures by visiting luminaries in science and literature,

to be held during sessions of Congress. The rest of the money would

be spent “accumulating a grand and noble public library; one which, for

variety, extent and wealth, shall be, equal to any now in the world.”

Despite being severely

ill on the day of the Institute’s dedication, Choate gave an eloquent address

that lasted for an hour and ten minutes, “without the listeners discerning

his suffering.” The topic of his speech was the “true idea and office

of the Lecture in connection with the library” which he perceived to be

“a means of intellectual culture.”

The library’s

first Lyceum Committee adopted Choate’s recommendation to have one or more

courses of lectures on some single subject from the same person.

Choate was known

as a great orator, a founder of the Whig party in the state and “the wizard

of the bar." When he argued cases at the Salem Court House,

crowds of people would wait outside and rush in to take their seats when

he began to speak. He once persuaded a jury to acquit a client of

a murder charge, pleading the crime was committed while the client was

sleep walking.

He opened his

law practice in the early 1800’s and went on to serve in the state legislature.

Eventually, he continued to the U.S. Congress to fill a seat vacated by

DANIEL

WEBSTER. Choate was an avid book collector, one of the early members

of the Danvers Literary Circle and of the town’s first Unitarian Church. |

About South Danvers (Peabody), Massachusetts

Marked by the traces of glaciers, the tidal basins of the Waters and

North rivers and numerous brooks, Peabody, Massachusetts emerged from the

witch hollows of Salem and the Revolutionary fervor of Danvers. Its

early history is inseparable from that of its eastern and northern neighbors.

The first settlers of “Brooksby”, the “Farmes” and parts of Salem Village,

arrived in 1626. They endured the intolerance of the Quaker persecution,

King Philip’s War and the trials of the witch hysteria.

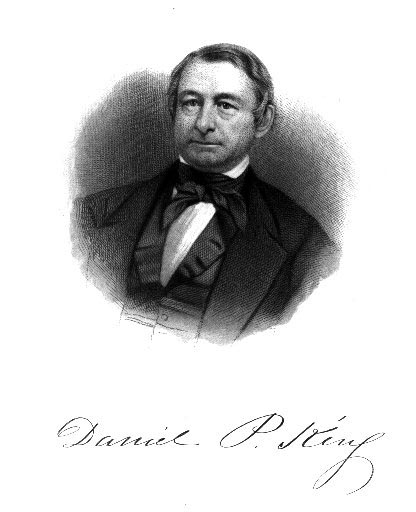

Fig. 4. 2. Map shows the locations of major landmarks,

farms, land grants, physical features, and the dwellings of promient and

important residents in Salem during 1692. The island in the lower left

corner is Humphry's Island in West Peabody.

A movement broke out at the turn of the eighteenth century for a separate

church for the village and in 1710 the Middle Precinct of Salem was formed.

In 1752, it was incorporated in the district of Danvers and was called

the southern village, or parish.

The second half of the nineteenth century brought residents increased

educational and economic opportunities that reinforced the cosmopolitan

picture of the area painted in the earlier part of the century by Washington

Irving.

In the Flowering of New England, he described a cultivated society

with “great square mansions” that “faced the sea or lined the stately

streets, with their beautiful gardens, cultivated by Scotch and Irish gardeners”.

He also reported that there were “notable scholars in charge of the young”

and that it was a “time of stirring intellectual life.”

In 1850, there were twelve, over-crowded district schools and two new

high schools. The moving force in town politics behind the move to create

a public high school was JOHN W. PROCTOR.

He was a lawyer and judge, as well as a long-time member of the Danvers

school committee. He evidently was also a supporter of educator HORACE

MANN, who was then the first Director of the state Board of the Education.

During his tenure, Mann managed to get a law passed that required towns

of a certain size population to provide a free high school. When the town

of Danvers did not abide by this new law, Proctor educated the townspeople

and succeeded in getting the town to vote to create two high schools, one

in the south and the other in the central part of Danvers.

“Local interests overpower mental needs – and because there is some

doubt just where to place a high school, the town sagely and illegally

heretofore have determined not to have any,” said Proctor. “So, if our

young men and women wish for higher than common education, they are obliged

to leave their home, and take their talents and energies elsewhere.

What thus the town may lose, cannot be calculated.”

At the same time that the town’s new high schools opened, a new bank,

the Danvers Savings Bank, opened its doors. It joined four other financial

institutions: Village Bank, Danvers Bank, Warren Bank, and the Danvers

Mutual Fire Insurance Company.

The temperature was sweltering on June 16, 1852 when twelve hundred

people gathered for a banquet under a large tent erected off Crowninshield

Street in the south village. The dinner marked the finale of a day

of spirited and patriotic observances to commemorate the one hundredth

anniversary of the separation of the town of Danvers from Salem, Massachusetts.

An elaborate parade that measured nearly a mile-and-a-half stepped off

at ten o’clock, passing triumphal arches of evergreens, flowers and flags

and including eight hand-pump fire engines and companies, contingents from

each of the public schools, and floats with a tableaux of scenes.

A cavalcade of three hundred horsemen promenaded through the streets to

the Old South Meeting House where three hours of services and choral

performances were held.

Fig. 4.3. The Square 1848.

A procession was formed and ticket holders walked to the “large canvas

pavilion” and entered under escort of the Military and Firemen.

After dinner was served, a lengthy “intellectual repast” was planned.

Fig. 4.5. Danvers Centennial

Celebration 1852.

One of the highlights

of the evening was the mystery surrounding a letter that had arrived from

London. It was from Danvers native and international merchant GEORGE

PEABODY. The town’s most famous son, Peabody was invited to the celebration

but declined the invitation. Instead, he sent a sealed letter with

instructions that it not be opened until the speeches were to be made at

the centennial event.

“…At the proper moment the reading of the

communication was called for; and the following was received by the delighted

audience with loud acclamations:

"By GEORGE PEABODY, of London;

EDUCATION – A debt due from present to future generations.

In acknowledgment of the payment of that debt by the generation which

preceded me in my native town of Danvers, and to aid in the prompt future

discharge, I give to the inhabitants of that town the sum of TWENTY THOUSAND

DOLLARS, for the promotion of knowledge and morality among them…..for the

purpose of establishing a Lyceum for the delivery of lectures, upon such

subjects as may be designated by a Committee of the town, free to all the

inhabitants...and that a library shall be obtained, which shall also be

free to the inhabitants."

The announcement caused a great stir. Although most of the people

in attendance were not personally familiar with George Peabody, a few recalled

knowing him in their youth and attributed his gift to education to the

value he placed on his limited education in common schools.

He was the third son in a poor family. For five years, between

the ages of seven and eleven, he attended one of the town’s two district

schools. The school was primitive and George attended only

for a few months when he could be spared from work at home.

By 1852, opportunities for higher education in the town of six thousand

people had improved. A special town meeting was held less than

two weeks after the gift was announced and it was voted unanimously to

accept the endowment and to name the institution “the Peabody Institute.”

The town followed Peabody’s advice and defined the Lyceum as an institution

where people could acquire knowledge and deemed that it not to be used

“for political ends or as a center of heated religious arguments.”

Twelve men were elected to serve on the Board of Trustees to oversee

the Institute’s funds and property and another board, the Lyceum and Library

Committee, was selected to direct the operations of the Institute.

The south village became the town of South Danvers

– eighty years after some citizens first called for a division between

the largely rural and port section of north Danvers and the manufacturing

center of southern Danvers. Legal and amicable on the surface, the

decision to divide was laden with heavy-handed politics.

Town meeting was held alternately at the high school in each section

of Danvers. In February 1855, it was held in the Peabody High School

on Stevens Street in the southern village. A resolution was presented

requesting the state Legislature divide the town using boundaries that

largely replicated the original bounds set in 1710 for the old Middle Precinct.

Several votes were taken and no agreement found. About seven o’clock,

residents voted 235 in favor of separation and 141 opposed. “It was

reported that voters from South Danvers kept delaying the meeting until

the hour of the final vote, as it was getting dark, and many of the farmers

of North Danvers had to leave to take care of their cows and chores.

So, some went and the vote went in favor of those who wanted to divide

the town.”

A month later, a special meeting was held in the North Parish to vote,

by ballot, on the petition of Benjamin Goodridge to divide the town.

“At this meeting, the advocates for division of South Danvers, relying

on the vote already secured, wisely let the day go by default, when they

refused to vote and the vote cast represented only the North Danvers vote.

The people of North Danvers appointed six men to oppose the division.”

The bounds of the village to the east were also changed. An act of the

Legislature passed on April 30 changed the ancient boundary between Salem

and South Danvers. Prior to the change, it was reported that the

line “ran through a house on Main Street, through a bedroom and across

a bed, so that the heads of the occupants were in Salem and their feet

in South Danvers.”

The new town of South Danvers had a population of 5,348 and a territory

of seventeen square miles. In May, 1855, an act to incorporate the town

of South Danvers was presented to the Governor and passed by the state

legislature. Fireworks and bonfires were part of the jubilant celebration

that followed the announcement in South Danvers, which represented the

larger part of the old town both in population and in valuation.

Three months later, George Peabody announced his plans to revisit the

United States. The town of Danvers voted to cooperate

with the new town of South Danvers to host a reception for Peabody. Two

committees were appointed to make arrangements in behalf of the old town

of Danvers, as it existed previous to the separation. The towns also

voted to equally share the expenses.

Reinforcing his reputation as a peace-keeper, Peabody accepted

the joint invitation of the town. Original plans calling for a low-key

celebration with “the feeling of a family meeting” were enlarged into a

grand event. The simple village festival became almost

national in character.

When the towns split, South Danvers had eight districts and sixteen

schools with 1,392 pupils and thirty teachers. The town paid

ten thousand dollars for the support of public schools, on a valuation

of three million dollars.

South Danvers included twenty-seven tanneries, twenty-four currying

shops, thirteen morocco shops and one patent leather factory. There

were twelve shoe manufacturers and five wool manufacturers, as well as

the Danvers Bleachery and the Davenport & Smith cotton mill.

Other industries included: three glue factories, two potteries, two bakeries,

two soap factories, a last factory, a box factory, four carriage builders

and working quarries. Dairy and farm products, including onions and

apples, constituted the town’s agricultural industries. The new town accounted

for seventy percent of the total valuation of the original town of Danvers.

.

|