Selected Verses from

NEW YEAR’S ADDRESS OF

THE CARRIERS OF THE SOUTH DANVERS WIZARD,

JAN. 1, 1864

The year is up!

Its hours have fled,

Old time his

year-glass turning,

Its passing days

are marked with red

In blood stains

of the worthy dead,

Their patriot

ardor burning.

The year is up

– the rebel strife

With scenes of

woe attended,

The wildering

din, the loss of life.

The muffled drum,

the screaming fife–

We trust are

well nigh ended.

We’ve told you

all that’s done and said

And who has done

the fighting,

The name of those

who fought and bled,

The poisoned

fangs of Copperhead

The nation’s

prospect blighting.

The entire poem is reprinted under

Literature

- Poetry.

A NEW YEAR’S GIFT

“Our population has

again been put under obligations to Mr. [George] Peabody by a munificent

donation of books, numbering 2,144 volumes… The news is proof of Mr. Peabody’s

interest in his native town, is not only gratifying for its increased means

of usefulness, but as a graceful intention that his fellow townsmen still

retain a warm place in his regards.”

(South

Danvers Wizard, 4/20/1864, p. 2/5)

Fig. 3. 3. Advertisement

|

Overview: January - July

1864

NEW YEAR’S

Fig. 3.1. The Peabody Institute, Peabody,

Mass.

The citizens of South

Danvers gathered at the Peabody Institute on Main Street to ring out 1863

with a Grand National Concert. Students in “Mr. Watts’ juvenile class”

sang patriotic songs such as “Zouaves Camp” and “When the War is Nearly

Over” and performed laughable farces entitled “The Flower of the Rebel

Army” and “The Raw Recruits.”

Four days later, crowds again visited the

Institute to attend a War Meeting. It featured the lively music of the

Salem Brass Band and patriotic speeches. Recruits signing on before

January 12 received an extra bounty from the town.

“Let Massachusetts and all other states make a New

Year’s present of their quotas to the army, and the hearts of not only

the suffering captives of Richmond, but many other loyal men, black as

well as white, all over the South, would be encouraged as they hear the

tramp of 30,000 more marching to their deliverance,” said lawyer and Peabody

Institute Trustee Alfred A. Abbott.

“To fail in this is to hold back the reserve that

is to win the battle. The prosperity of this part of the country

would depart, and we should see our land rent with civil feuds, and drenched

in fraternal blood: We are enjoying prosperity such as was never before

known in civil war. And shall we make return for this by folding

our arms, or shall we sacrifice all, our life, if may be, to the cause

of those at home. He would leave it to the wives and mothers of our

brave soldiers to say whether we should give up now. We must succeed,

for God never let anything so precious as patriot blood be lost.”

Fig. 3.2. Alfred A. Abbott.

As in many industrial

areas of the north, South Danvers was prospering in 1864. Local tanneries

imported 30,000 more hides than the year before. The Danvers Bleachery

on Foster Street was set to expand by adding dyeing and napping facilities.

The W. M. Jacobs & Son tannery announced plans to level its site near

Eagle Corner [Washington and Main streets] and build a new four-story factory.

The Eastern Railroad, which posted an 8.25 percent

increase in earnings in 1863, ran a special late train during that winter

in order to afford South Danvers citizens an opportunity to attend the

New York and Havanna Opera Troupe at the Boston Theatre. A successful

Antiquarian Supper and Levee, fairs and sleigh rides were popular, as well

as the use of laughing gas.

As the town’s prosperity grew so did the cost of

living and members of the working classes found it increasingly difficult.

The town’s vital statistics for 1863 indicate that of 150 births that year,

78 of the newborns were children of “foreign-born” parentage.

Of the 100 deaths that year, nearly half (47) were children under 8 years

of age.

By the end of January, the curriers in South Danvers

and Salem called a strike. A letter-to-the-editor signed by “Looker-On”

reads, “So far as the curriers simply ask for a rise in the price of labor,

corresponding to the rise in the price of necessaries of life, they are

clearly right; but when they attempt to dictate to their employers as to

the manner in which they shall carry on their business – what laborers

they shall employ – how many apprentices they shall have, etc. – they are

just as clearly wrong.”

The Journeyman Curriers of Salem and South Danvers were

supported early on by curriers in New York and New Jersey. By March,

the strike involved violence and intimidation.

Despite the three-month-long strike, the business of tanning

and currying continued to prosper and in April the

Wizard reported,

“The strikers are generally falling back into their old places, or going

into other business, so that street idlers are getting much more rare.”

Additionally, the strike resulted in “American workmen” filling “the places

vacated by foreigners.”

Another issue that separated the owners from the

laborers was the availability of inexpensive transportation. At town

meeting in February, citizens opposed a petition from the Eastern Railroad

to consolidate the South Reading Branch Railroad and endorsed a proposal

of the Salem and South Danvers Railroad for a charter for a road in Danvers

and for a petition for a Horse Railroad from South Danvers to Lynn.

The voters retained the right to demand the enterprise “be in the hands

of those who are identified with the local interests and business, and

will make it subservient to the prosperity of South Danvers and Lynn, and

not under the control of men or corporations who would undertake it for

speculative purposes…”

One letter-to-the-editor charged that opposition

to the proposed horse railroad route was voiced by “some six to eight men

in this town who keep a number of fancy horses, and who have but little

else to do but exercise them by driving to Salem and back two or three

times every day…Shall ninety-nine one-hundredths of the inhabitants of

the town of Danvers be put to trouble and expense daily on account of the

present impracticable mode of conveyance to Salem in order that the pleasure

and interests of some few may be gratified and enhanced?”

It was late May before the state Legislature granted

the petition to place track on Washington and Bridge streets, “in view

of running the cars to Danvers, over the main road”.

In June, the existing Horse Railroad raised its rates to six cents per

single ticket. The rate hike was justified due to the high cost of

meal, hay and upkeep for the horses. The following week, the Horse

Railroad donated a third of the fares collected to benefit soldiers in

hospitals.

Another “specimen of the rich trampling upon the

rights of the poor” arose in April, when the high price of butter placed

it out of reach of poor families. The price hike was blamed on “speculators

who have been shipping vast quantities to Europe to pay for imported gewgaws…”

A pledge was proposed for circulation among families, “whereby they agree

to abstain from the use of butter altogether, until it comes down to a

fair price.”

The spring was marked by unusual weather. Snow fell in

early April sufficient for sleighing. Tricked by the weather,

wild geese “commenced their spring campaign too early” and had to return

South. By mid-May, the temperature was near 90 degrees and

extreme heat, “up to 100 degrees in the shade” was recorded in late June.

The full moon that appeared at the end of June was so bright that residents

near Eagle Corner falsely reported the “bright light in a southwesterly

direction” as a fire.

Throughout the late spring of 1864, people in South

Danvers harbored hopeful feelings about the outcome of the war. The

Union victories in late 1863 at Vicksburg and Chattanooga, the relative

inactivity of the Army of the Potomac, and the assignment of Ulysses Grant

as Major General all added to the north’s optimism.

In February, President Abraham Lincoln called

for 500,000 more men to fill the ranks of the Union Army. The requisite

number of local men was easily found, as recorded in a Wizard editorial:

“It is now stated as a fixed fact that South Danvers is nine men short

of filling her quotas, and Danvers, forty in excess. The latter must

be a good place for those dreading a draft to live in.”

By mid-summer, the war assumed a more terrible

nature, eliciting deep despair. As the reports were received of the losses

resulting from six weeks of the bloodiest fighting, from the Wilderness

to Petersburg, the patriotic rivalry between the two towns took on a grisly

nature. The lists of recruits previously published in the paper were

replaced with lengthy lists of dead men from the towns.

A note at the bottom of the list of Danvers

men reads, “It will be seen that the above list contains the names of fifty-four

soldiers, who have been killed in battle or died while in the United States

service, this is a loss of eighteen greater than that of our neighbor town,

South Danvers, and probably larger than that of any other town in Essex

County, in proportion to its population.”

Symbolizing both the hope and weary resignation

of the townspeople towards the war is the record of MOSES SHACKLEY, JR.,

a graduate of Peabody High School. His story is recorded in the pages of

the Wizard beginning in 1861, when he joined the Army at the age

of 17.

At the town's first war meeting, Shackley's

father, a member of the committee of five selected by the townspeople

to meet the call for troops, announced that he "had already fitted out

and sent his son at an expense of fifty dollars. This allusion to

the young and patriotic Shackley ... brought down the house with deafening

applause."

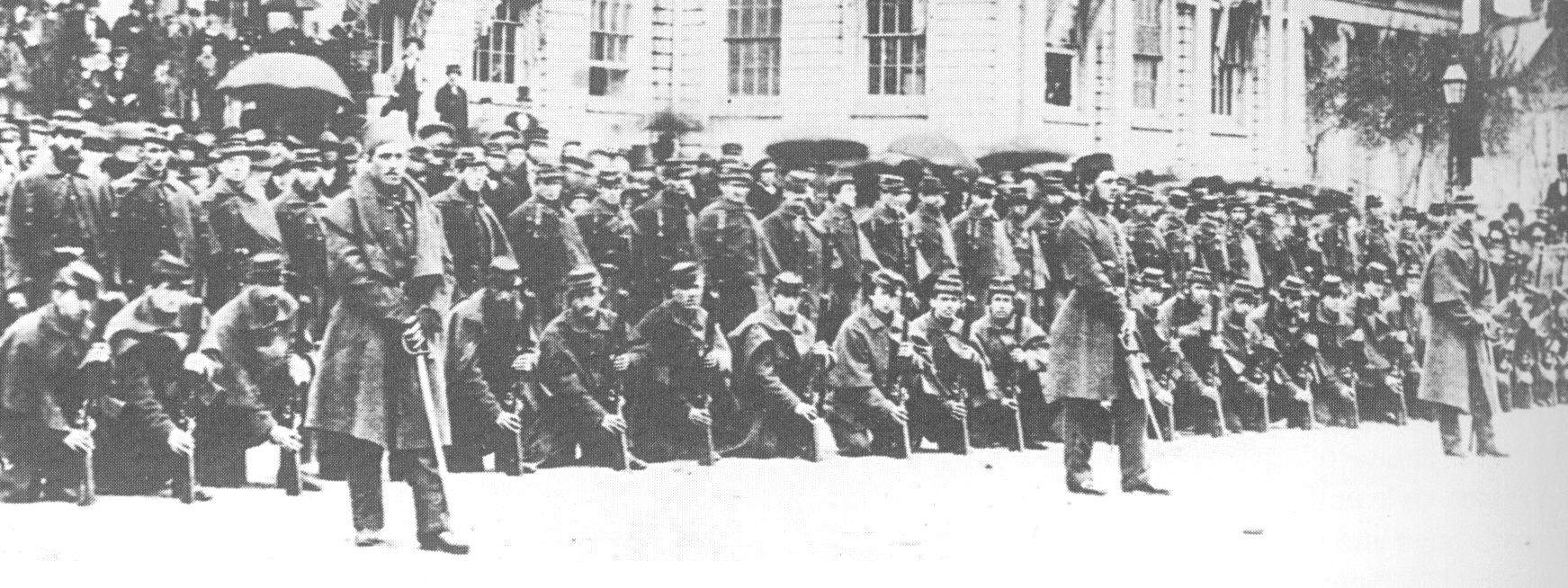

Fig. 3.4. Company A, 8th Massachusetts Regiment, known

as the Salem Zouaves.

Shackley enlisted before

the onset of the war as a 3-months man with the Salem Zouaves of the Massachusetts

8th Regiment. He was on his way, he thought, to Baltimore, Maryland

to protect the Capitol. He was routed not to Baltimore, but to Annapolis

to protect Old Ironsides and was among the troops that arrived at Washington

shipyard and marched to the capitol building. In August, he made a visit

home and was reassigned as a wagoner to the Massachusetts

19th Regiment. He soon left the wagons and went into the ranks.

By September, he was stationed at Harrison's Landing on the James River

in Virginia and participated in the seven days fighting before Richmond.

He earned a Lieutenant's commission by his

bravery and participation in the bloody encounters of Ball's Bluff (Harrison's

Landing), the battles of the Peninsula, second Bull Run (Manassas), Antietam,

Fredericksburg (Marye's Heights), and at Gettysburg, where he distinguished

himself.

When a battery was disabled while under terrific

cannonading, volunteers were sought to assist in working its guns.

The Adjutant General reported, "The conduct of Second Lieutenant Moses

Shackley, who insisted on joining the volunteers, was particularly gallant

and brave, walking from piece to piece, encouraging and assisting the men."

Shackley remained with his regiment some five months

after the battle of Gettysburg, when, his well-earned rank was reduced

in what was reported as a "mean attempt to injure his reputation." He returned

to South Danvers and an editorial appeared in the Wizard in December,

1863. It reported that Shackley was absent without leave from the

Army and was discharged. "Such services in the foremost positions

in actual warfare deserve honorable mention, and its only for those who

have done more in the great cause of the country to speak in terms of disparagement,"

it read.

Twenty-year-old Shackley did not remain inactive

for long. When the call for more troops was issued in the winter of 1863,

he enlisted at a lower grade in the 59th Veteran Corps, and, under generals

Burnside and Gould, he fought safely at the Wilderness and was mortally

wounded in the Bloody Angle at Spottsylvania Court House on May 12, 1864.

He died the next morning at the camp hospital.

“Of all who have gone out from us, few have

fought so many battles and encountered so many perils, and at the same

time endured the fatigues of the camp as cheerfully as our departed friend

and townsman,” read the editor’s note preceding the article that appeared

in the Wizard on June 1.

Another loss felt by the town was the death

of local author NATHANIEL HAWTHORNE in May. An obituary by “H.D.J.”

appeared in the Wizard. The author reported that “[We/I] have

listened with admiration to his sublime and instructive conversation.

He was mentally sensitive in the extreme. He never seemed to appreciate

the great power of his own genius.”

Hawthorne’s career and writing was a topic

of continued coverage in the Wizard. Editor Fitch Poole, Jr.

reviewed Hawthorne’s book “Marble Faun” in a May 1860 issue of the paper.

A report penned by Hawthorne and providing an account of the battle of

the ironclads, the Monitor and the Merrimac, appeared in the Wizard

in July 1862.

Since its inception, it was a habit of the

Wizard

to

feature all news published about GEORGE PEABODY, the town’s benefactor.

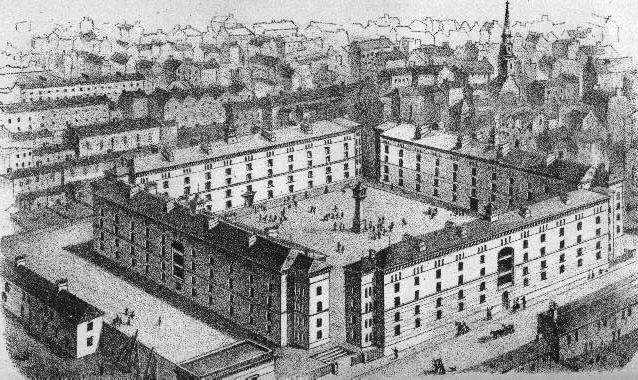

The town received news in late January that “the trustees of Mr. George

Peabody’s munificent gift of 150,000 to the poor of London, have decided

to appropriate the fund, or the large part of it, to the erection of buildings

in suitable localities to furnish lodgings for the poor. One of the

proposed buildings has already been finished, and the lodgings are about

to be let. It is four stories high covering an area of 30,000 square

feet. It contains, besides stores upon the street…”

Fig. 3. 5. Peabody Square, Islington, London.

The following month, the

Wizard

reported that “Five hundred thousand dollars of the Coast Defence scrip

of Massachusetts has been taken by George Peabody, of London, at $110.”

In late spring, the Wizard reported

that George Peabody donated $500 to the Baltimore Sanitary Fair.

A month later, Peabody announced he would retire in October from George

Peabody and Company.

Much of his time was occupied with plans

for the Peabody Donation Fund, “for the benefit of the industrious poor”.

Eventually, the endowment became the Peabody Education Fund, which directed

its efforts to provide education in the southern United States.

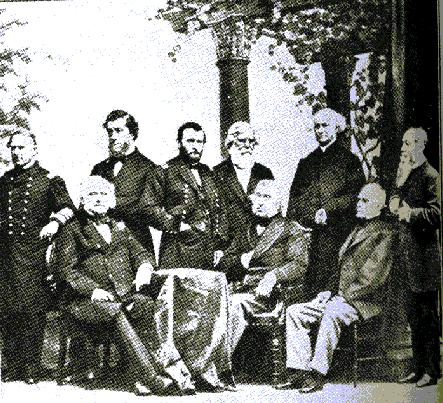

Fig. 3. 6 Peabody Fund Commission - Admiral [David]

Farragut, George Peabody, Hamilton Fish,

General [Ulysses] Grant, Governor Aiken, S.C., Robert

Winthrop, Samuel Wetmore

1. “Another War Meeting.”

South Danvers Wizard

6 Jan. 1864: 2.

2. “Grand National Concert.”

South Danvers Wizard

6 Jan. 1864: 2.

3. “New Dye House.” South Danvers Wizard 9 Mar.

1864: 2.

4. “Improvements.” South Danvers Wizard 1 Jun.

1864: 2.

5. “Amusements in Boston.”

South Danvers Wizard

13 Jan. 1864: 3.

6. “Laughing Gas.”

South Danvers Wizard

2 Mar. 1864: 2.

7. “Births, Marriages, and Deaths in South Danvers

in 1863.” South Danvers Wizard 17 Feb. 1864: 2.

8. “The Strike.” South Danvers Wizard 27 Jan.

1864: 2.

9. “Assault and Battery.”

South Danvers Wizard

9 Mar. 1864: 2.

10. “Tanning and Currying.”

South Danvers Wizard

13 Apr.1864: 2.

11. “Town Meeting.” South Danvers Wizard 3 Feb.1864:

2.

12. “Danvers vs. Horse Railroad.”

South Danvers Wizard

17

Feb.1864: 2.

13. “The Horse Railroad Hearing.” South Danvers Wizard

15 May 1864: 2.

14. “Fare Raised.” South Danvers Wizard 1 Jun.

1864: 2.

15. “Soldiers’ Aid.” South Danvers Wizard 8 Jun.1864:

2.

16. “Butter Pledge.” South Danvers Wizard 13 Apr.

1864: 2.

17. “Sleighing in April.”

South Danvers Wizard 13

Apr.1864: 2.

18. “Wild Geese.” South Danvers Wizard 13 Apr.

1864: 2.

19. “Alarm of Fire.” South Danvers Wizard 22 Jun.

1864: 2. |